Policy 2071: How Do We Help Rural America Thrive?

In Washington, D.C., and state capitals across the country, housing policies are being put in place that will leave an indelible mark on the future of rural communities. Although 2071 is far away, housers are already working to craft a federal policy strategy that will help rural communities succeed for the next half century and beyond.

The Housing Assistance Council (HAC) uses the lessons we have learned over 50 years of service to give a voice to rural communities and to shed light on how the most persistently poor rural areas can share in the nation’s prosperity. Since 1971, HAC has helped build homes and communities across rural America. Through the Vision 2071 campaign, we look toward the next 50 years.

If we want rural communities to thrive over the long term, we need to understand how our policy decisions today impact the reality of tomorrow. We asked eight experts to share their vision for how federal housing policy could solve the toughest challenges facing rural America. They put forward approaches that incorporate strategy, funding, and flexibility that deepen local capacity, lift up the natural advantages found in rural places, and result in a coordinated set of federal policies designed purposefully for small towns and rural regions.

Experts

Challenges

To address the challenges facing rural housing policy, those challenges must first be identified. Tony Pipa is a Senior Fellow in the Center for Sustainable Development at the Brookings Institution. He says that “there is no single federal rural housing policy.” Instead, rural housing is supported through a patchwork of programs spread across multiple departments, each attempting to fit rural housing into its own broader goals. The absence of a unified, coherent federal rural housing policy results in a failure to address comprehensively the lack of funding, dearth of housing stock, and interlocking challenges faced by rural communities.

Funding

Federal rural housing programs are impactful, but many lack the funds they need to fully realize their potential. For 25 years, Colleen Fisher has served as the Executive Director of the Council for Affordable and Rural Housing, a national nonprofit trade organization for the affordable rural rental housing industry. To her, the greatest challenge facing rural housing “is funding.” The federal government has already developed programs with proven positive impact, but these programs just are not funded adequately.

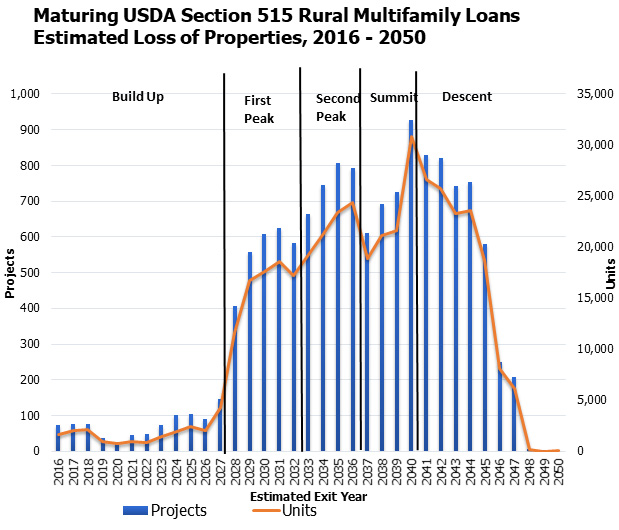

Take for example, the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s (USDA) Section 515 program. Under the program, the USDA provides mortgage lending for affordable rental housing. Once the homes are built, they are eligible for USDA rental assistance. However, without major investment in preserving Section 515 housing, affordable rental homes are leaving the USDA’s portfolio, often losing their rental assistance and affordability protections at the same time. Fisher points to recent funding efforts to preserve existing Section 515 homes and build more as cause for hope. Sadly, they have stalled along with the rest of the Build Back Better Act in the Senate.

Hundreds of thousands of homes are expected to leave USDA’s Section 515 portfolio by 2050, losing their rental assistance and affordability protections.

Hundreds of thousands of homes are expected to leave USDA’s Section 515 portfolio by 2050, losing their rental assistance and affordability protections.

There are similar problems with most federal rural housing programs, says Gideon Anders, the former Executive Director and current Senior Staff Attorney at the National Housing Law Project. He has served on HAC’s Board of Directors for over 28 years. “We just haven’t had any commitment to fund what is needed.” Rural America faces a crisis of affordability—2.6 million rural families pay more than half their income on housing. Anders emphasizes that federal programs are powerful tools to improve housing affordability, but only when funded adequately. “We have to increase the amount of subsidy” we invest in rural affordable housing, he argues. Otherwise, deteriorating housing stock and rising prices will continue to exclude low- and moderate-income families from having decent, affordable homes.

Housing Stock

Rural communities lack the housing supply to fully meet current needs, let alone those of the next 50 years. Bob Rapoza, the Founder and President of Rapoza Associates and Executive Secretary of the National Rural Housing Coalition, has over four decades of experience as a lobbyist, with expertise in federal housing and community development policy. According to him, rural America has seen construction of new homes fall by about 2/3 since before the Great Recession. This slow-down in construction is already increasing prices. “If supply is down, competition is keener, and low-income families will have the hardest time” finding affordable places to call home.

Andres Saavedra is a former Program Director at the Local Initiatives Support Corporation (LISC) and is a former member of HAC’s Board of Directors. He describes that the reduction in supply also poses a serious long-term risk. With few new homes being built and existing affordable housing not being preserved, we are barreling towards a housing crisis that will particularly affect low-income seniors. As he notes, we do not have a good answer to a basic question: “Where is grandma going to live?”

Gbenga Ajilore, a past president of the National Economic Association, serves as a senior advisor in the Office of the Under Secretary for Rural Development at USDA. To him, the problem is not just that we have too few homes; our housing stock is not prepared to meet the challenge posed by climate change. For example, many affordable homes are in flood zones, even though “we figured out a long time ago that building in flood zones is a bad idea.” “Rising climate risk” already threatens our communities through more intense wildfires and hurricanes, he observes. What we lack is what Ajilore calls “adaptive housing,” homes built to withstand the climate risks of their location.

Interlocking Challenges

The greatest policy challenge for rural housing is “that there isn’t one greatest challenge,” explains Pipa. Rural America faces “diverse challenges affecting diverse communities.” From affordability to housing quality, homeownership rates, and racial equity, rural communities face a variety of challenges. It is hard for one policy to address this array of issues in a range of places.

Patrice Kunesh established and led the Center for Indian Country Development at the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis and served as Deputy Under Secretary for Rural Development at USDA. She now works as the Major Gifts Officer at the Native American Rights Fund and Director of Peȟiŋ Haha Consulting. She adds that the problems facing rural communities are all interrelated. Housing supply, the quality of housing stock, affordability, and local capacity are so intertwined that “we can’t put one over the others” if we want to solve any. However, American housing policy often overlooks the unique ways that rural challenges interlock.

This lack of recognition is exactly the problem, argues Elsie Meeks, who served for six years as the USDA Rural Development State Director for South Dakota. A former member of the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights, she has also led Oweesta Corporation, the longest-standing intermediary for Native community development financial institutions (CDFIs). If there are ever going to be policy solutions, she says, we need “a recognition that rural housing is challenged by” a variety of problems.

The Jamie L. Whitten Building, headquarters of the U.S. Department of Agriculture. USDA operates numerous rural housing and community development programs.

A Coordinated Federal Policy for

Rural Housing

Every expert noted that what rural America needs is a coordinated federal response, one that works across departments and programs to help rural America overcome its challenges holistically. So, what should this coordinated federal strategy entail? To help build long-term solutions that will help rural America thrive over the next 50 years, we need unified strategy, funding, and flexibility.

Strategy

The primary benefit of a unified federal strategy is that it allows policymakers to “invest for the future rather than [focus only on] keeping people’s heads above water,” Tony Pipa explains. To Elsie Meeks, this long-term thinking is critical. As she adds, USDA housing programs typically plan about five years ahead. If policymakers from multiple departments could plan together 20 or 30 years ahead (which a coordinated strategy would help them do), communities could plan more proactively and more economically to meet their needs.

Just as important as ensuring federal policy is coordinated and coherent, though, is making sure each policy and program shares the same goals and objectives. To develop a national strategy, policymakers must ask a crucial question: what are the underlying problems facing rural communities, and how will our programs contribute to a solution?

By creating a unified federal strategy for rural housing and aligning programs to support that strategy, we can build a rural America “that is thriving” but where each community “thrives in its own way,” notes Gbenga Ajilore. To Ajilore, the driving principle of rural housing policy should be ensuring that anyone can live in a town of 10,000 without having to settle for less access to community facilities, slower internet, low wages, or poor housing. In other words, “valuing rural places and the people in them” must be at the heart of our purposeful efforts to help them succeed.

Funding

The most obvious cornerstone of this unified federal policy is dedicated, consistent funding. As Colleen Fisher lays out, “housing is expensive, no matter how you put it.” We must be willing to make that investment if we want the benefits of more quality, affordable homes for rural Americans to live in. Fisher notes that the cost of acting is actually lower than leaving the system as is. She describes that while it would take billions of dollars to preserve the affordable homes in the USDA’s Section 515 portfolio, many more billions would be needed to build new affordable homes to replace a lost portfolio.

“The federal government ought to do a lot more,” but that requires resources, says Bob Rapoza. Over the past 20 years, spending on rural housing loan programs to finance homeownership, rental housing, and home repair have been reduced by over 60 percent when adjusted for inflation. Funding that is reliable and sufficient would help the government scale up its housing programs, making them even more effective. “Federal programs depend on scale” to reach more Americans at a lower price, so “a dependable flow of funds for federal housing programs” at USDA and the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) would make a substantial difference.

Increasing federal spending will likely require increasing revenue. Gideon Anders argues that the federal government can both raise revenue and improve housing equity by repealing the mortgage interest deduction. Under current tax code, the interest homeowners pay on mortgages is tax deductible only for those wealthy enough to itemize their deductions. Low- and moderate-income families almost always take the standard deduction, however, Anders explains. The effect of the mortgage interest deduction, then, is to subsize billions of dollars per year of the housing costs of higher-income households, money that Anders suggests could be better spent funding much-needed housing programs.

Flexibility

In addition to large-scale funding solutions, Saavedra encourages us to “think small” when it comes to rural housing policy. While building large projects in rural communities rarely makes sense, we can achieve scale through larger numbers of smaller projects. A flexible system of development that builds “six units here, 10 units there” will make the difference in every community in which it is used.

One way to improve both the flexibility of federal programs and their effectiveness is by investing in CDFIs, Patrice Kunesh adds. To scale up construction, we need thriving systems of capital to fund that construction. Because CDFIs work closely with their communities, investing in them can get money closer to the end beneficiaries. “Communities know what to do” when they have funding, so let’s empower them, Kunesh argues.

The U.S. Capitol and surrounding buildings. Addressing rural America’s challenges requires a coordinated strategy across the entire federal government.

Sustaining a Long-Term Vision

The policy challenges facing rural America have policy solutions. However, those solutions rely on all of us—policymakers, housers, and residents—to sustain them and to make them truly work for our communities. Rural America’s success will be shaped and driven by our vision for the future. To make long-term solutions possible, rural America needs equally long-term commitment, meaningful partnerships, and new paradigms for how we build our communities. It takes political will for each new presidential administration to design and launch anti-poverty measures. Although it takes far more will, it is almost always more fiscally responsible, efficient, and effective approach to better fund and administer the programs already in place.

Commitment

The solutions being proposed to strengthen rural America are not novel. As Gbenga Ajilore contends, enacting these policies requires concentrated political will. Sustaining long-term solutions requires equally long-term commitment—from policymakers and from voters. “Poverty is a policy choice,” he notes. The long-term decision to end it is also a choice. Elsie Meeks cautions that this commitment to funding needed programs cannot come just from the federal government. State and local governments fund housing development and decide crucial policies like zoning. Their commitment will be equally important to solving rural communities’ housing challenges.

Looking ahead to 2071, Tony Pipa proposes that we learn from the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals, which offer 17 benchmarks to building more sustainable communities worldwide. Setting measurable goals would help to channel our commitment and focus our efforts. Like the U.N. Sustainable Development Goals, our national goals for rural communities would emphasize the “interconnectedness and interdependence” of every part of our communities. After all, housing is “central to education, health, and the ability to be economically active.” By focusing on “housing as a key social good,” our commitment to house our neighbors can be placed in the context of broader commitments to build stronger communities.

Partnership

As America works to sustain a vision for rural prosperity over 50 years, it will require partnership within rural communities and outside them. According to Andres Saavedra, rural housing advocates and rural agricultural groups have not always worked together. However, each movement is rooted in the mission of improving rural communities. Combining efforts could help both to succeed. Similarly, the rural housing movement could find valuable allies in the racial justice movement, Saavedra adds. By building bridges between housers and advocates for minority communities, we can both strengthen our movement and lend our strength to efforts to make America more just and equitable.

Colleen Fisher contends that building a national movement requires us to make the case to a national audience. Homes are a deeply personal issue, so she proposes we highlight the importance of homes to families. “Rural housing naturally tells a story.” Every time a new family moves into an affordable home, we have the opportunity to ask our audience, “if this family didn’t have this home, where would they be?”

In 2020, a coalition of community members and designers worked with a CDFI to rehab 27 homes and build 13 new homes outside Moorhead, Mississippi. Johnny Carter poses for a portrait in his new home. Rory Doyle/There Is More Work To Be Done

New Paradigms

Our policy experts were clear that ambitious visions for rural success will require new paradigms for how we build community. According to Patrice Kunesh, achieving long-term housing goals requires a “transformation of mindset” to recognize that “everything that makes a community revolves around housing.” She suggests a strategy that incorporates building the wealth of families and incorporating housing into other community-building efforts.

New strategies for federal programs are also needed. Bob Rapoza proposes that in addition to massively scaling up federal housing investment to meet current needs, federal programs must figure out “how to create a structure that reaches people” where they are. Decades ago, the USDA established local field offices so families “could walk in and get a loan.” With the current lower staffing levels of federal housing programs, that ideal no longer exists, so finding new ways to reach families will be critical.

Gideon Anders argues that the most important paradigm shift would be enshrining a right to housing. It’s only with a large-scale, universal commitment to every American having a home that we’ll be able to “solve the problems that are facing rural and urban communities,” he says. He proposes ensuring everyone can receive a housing voucher that can be used for rental housing and homeownership. In addition, federal programs need to recognize “that homeowners and renters will always face hardships.” Rather than just trying to prevent those hardships, we need more federal tools to help “keep those hardships from leading to foreclosures and evictions.”

Conclusion

The next 50 years of rural America will be shaped by the housing policies we enact today. Federal policy is a powerful tool to steer our nation in the direction of positive change. Just as federal policy shaped the present, it will shape the future. That’s why HAC celebrates our 50th anniversary by outlining our policy priorities for the next 50 years.

This is not the first time that any of these policies have been proposed. As Gideon Anders notes, housing advocate and policy expert Cushing Dolbeare advocated for robust federal investment in rural housing and the elimination of the mortgage interest deduction in the 1970s.

The vision of our policy experts is one of thriving rural communities, where opportunities abound and homes are safe, accessible, and affordable. The policy solution they propose—a coordinated federal plan that incorporates strategy, funding, and flexibility—could make that vision a reality. As Gbenga Ajilore posed it, “We know how to get there. The question is whether we have the will.”